Shamatha technique for peace of mind audiobook. Mindrolling is a Buddhist monastery in Dehradun. Briefly about the program

Hello, dear Reader.

Our story today is about how to achieve a state of concentration, clarity and transparency of the mind, and get rid of delusions.

If we go back 2,500 years, we can say that the very foundations of Buddhism originated in meditation. Legend claims that by plunging into a state freed from thoughts and the sensory side, the Buddha was able to achieve Enlightenment. It was this event that gave rise to a new philosophical teaching. The shamatha (samadha) meditation technique is one of the most accessible practices used in all areas of Buddhism without exception. It is quite simple and natural for a human being.

Basics

Meditation– this is a special type of mental exercise in spiritual practice or performed for health purposes. The end result of such activities is the clarification and pacification of the mind, getting rid of delusions and fears that prevent one from seeing objective reality, and achieving a state of mental peace. The technique is quite simple, and with regular practice, the shamatha state can be achieved within a few months.

Principles

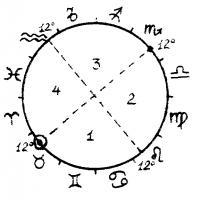

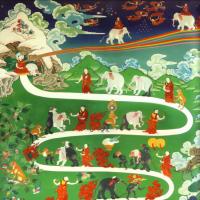

The Buddha compared mastering the shamatha technique to taming a wild elephant. The stages of the meditator's path are reflected in the form of an image in the famous Tibetan woodcut. It was created by the Teacher of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Trijang Rimpoche.

The curves of the difficult path in the image are not accidental and symbolic; they mean six important principles that everyone who has begun the path of shamatha must adhere to:

- receiving recommendations and instructions;

- mastering acquired skills;

- repetition;

- attention and alertness of mind;

- continuity and persistence;

- state of perfection.

steps

Nine images characterize the same number of steps of shamatha. In an allegorical and visual form, changes in the state of mind and consciousness of the one who began the difficult path to comprehending the Truth are reflected: a monk whose hands hold a lasso and a hook, a monkey and an elephant.

The play of colors, black and white images is a step-by-step path to peace and getting rid of delusions that close the mind. The lasso is a symbol of mindfulness and awareness, the hook is a symbol of vigilance, the elephant is consciousness, which is colored black at the beginning of the path, and the monkey is a symbol of a wandering mind.

The deep meaning inherent in the series of images can be stated as follows: in order for black to become white, in order to achieve awareness, it is necessary to throw a lasso over consciousness and, hooking it with the hook of vigilance, lead it to Liberation. Only this way will help calm the wandering mind.

You cannot achieve Samadhi without going through all nine steps. Consistently replacing each other. Tibetan woodcut images reflect these stages:

- At the very beginning of the path, the seeker of Enlightenment is at a great distance from his mind. There are too many obstacles, the elephant follows the monkey.

- Attention helps the meditator get closer to the elephant; through the blackness, white spots can be seen on the monkey, which symbolizes a decrease in mental arousal.

- The meditator and his mind have met closely and are no longer moving away from each other, although the monkey is still ahead and is trying to pull the elephant behind him.

- The gap between the mind and the meditator is reduced even further. There is a lot more white in the picture.

- The roles change, and the meditator now walks in front of the elephant, leading it along.

- There is no need to control attention. The return of meditation is inevitable, the mind is controlled by consciousness.

- Almost complete control, only small dark spots indicate minor obstacles on the path to Realization.

- Natural and continuous meditation that does not require much effort.

- The shamatha practitioner and the elephant, symbolizing the mind, are in complete peace. They are next to each other and there is nothing that can prevent this union. Shamatha has been achieved.

On the path to understanding shamatha, consistent movement is of utmost importance. At each stage described, a stop is required to improve skills.

Shamatha is a state of peace and serenity, the ability to contemplate the real world without the exciting influence of the mind.

Start

Before practicing shamatha meditation, you need to determine for yourself three things that matter:

- place;

- correct posture;

- object selection.

Place

In order to start practice, it is not at all necessary to retire to an abandoned corner, choosing a deep forest or mountains. It is enough to find a convenient, comfortable room where no one can disturb the peace.

Position

Posture is also important. Of course, it is good if this is a sitting position with crossed legs, however, not everyone will find it comfortable, so for a beginner it is recommended to take a comfortable sitting position.

The position of the hands is also important: they should be located at the level of the stomach, the right one on top of the left, with the thumbs touching each other. The back is straight and not tense, the tongue is pressed to the upper palate, the eyes are relaxed and slightly closed.

An object

In the shamatha technique, the substrate on which attention will be concentrated can be the breath (this is exactly the practice that Buddha spoke about) or any object suitable for visualization.

Focusing on breathing movements is one of the simplest meditation techniques. During practice, you need to keep your attention only on the movements of the chest - inhalation and exhalation, without allowing your consciousness to switch to other objects, thoughts or actions.

If an agitated mind distracts attention, you should return to the starting point and again try to concentrate, discarding extraneous external and internal irritants. After a short time, with regularity and perseverance, you will notice that it becomes easier to concentrate and control the wandering of thoughts.

The shamatha technique is the foundation on which other Buddhist practices are based. Without mastering it, there is no movement towards tantra, mahamudra, dzogchen.

Possible mistakes

The path through all the stages in order to achieve shamatha can be compared to the flight of an eagle. To take off, he uses the force of flapping his wings, but, having reached the desired height, he simply soars without putting much effort into it. To achieve freedom, you should know the five mistakes of meditation and ways to avoid them.

The vices that prevent you from taking off and soaring are:

- Laziness. The most common mistake.

- Distraction from the object. The reason for this is a disobedient wandering excited mind. The meditator forgets the object with which the meditation is connected.

- Restlessness and loss of clarity of thought.

- The “antidote” is not applied when it needs to be applied.

- An "antidote" is used when it is not needed.

You can achieve progress by avoiding the listed mistakes. Here is a list of “antidotes” necessary for use. Their number reaches seven, and the first four are salvations from laziness:

- Faith. A sincere belief that achieving shamatha will bring great benefits.

- Inspiration. It is directly related to belief, because it is this that generates the desire to engage in meditative practice.

- Pleasure. It arises from the first two, because faith and inspiration are the trigger for the emergence of enthusiasm and pleasure.

- Achieving peace of mind.

- Attention. This “antidote” helps to concentrate on the object of meditation and avoid the second mistake.

- Vigilance. Helps control states of extreme agitation or loss of lucidity. There are special meditative skills that help you maintain the flow of consciousness.

- Be able to let go of the mind. A similar skill helps with the fifth error of meditation.

Shamatha as a self-development technique

Even for people who are far from religious views, the shamatha technique can bring invaluable benefits, leading to peace of mind and increasing personal effectiveness. It has pronounced therapeutic properties in our difficult age of emotions and endless stress.

Conclusion

Dear Reader, if you are interested in the topic of our article, share it on social networks. And we say goodbye until the next time on the blog!

In the process of meditation we constantly discover who and what we are. This may cause fear or boredom, but after a while, it goes away. We fall into a kind of natural rhythm and discover our fundamental mind and heart.

Meditation often seems to us like something unusual, some kind of sacred spiritual activity. This is one of the main obstacles that we try to overcome during practice. The point is that meditation is a completely natural process; it is the quality of mindfulness present in everything we do.

This is a simple law, but we constantly deviate from our natural state, our natural being. During the day, anything takes us away from our natural mindfulness, from being in the present moment. Our natural tendency to rush means that we rush past past opportunities. We were too scared or too worried about something, too proud or simply too crazy to be ourselves.

This is what we call a journey or path: a constant quest to understand that we can, in general, relax and be ourselves. Thus, the practice of meditation begins with simplifying everything. We sit on a pillow, watch our breathing and watch our thoughts. We simplify everything that happens.

Shamatha/Vipasana Meditation, sitting meditation is the foundation of the path. If you are not able to contact your mind and body on a very simple level, it is not possible to practice the higher teachings. Ordinary sitting is how the Buddha himself came to become a Buddha. He sat under a tree and did not move. He practiced exactly the same as us.

We are engaged in pacifying our mind. We are trying to overcome various types of anxiety and worry, habitual thought patterns in order to be able to sit alone with ourselves. Life is difficult, we may have a huge responsibility, but the strange thing, the paradoxical logic, is that the method by which we try to connect with the mainstream of our life is by sitting completely still. It seemed like it would be more logical to hurry up, but we're simplifying everything down to a very simple basic level.

We quiet our mind using mindfulness techniques. Very simply: mindfulness is complete attention to all details. We are completely absorbed in the structure of life, the structure of the moment. We realize that our lives are made of these moments and that we cannot live several moments at a time. Even though we have memories of the past and ideas about the future, the experiences we have are in the present.

In this way we can experience our life completely. We may believe that we are enriching our lives by thinking about the past or the future, but by not paying attention to what is happening in the present moment, we are actually missing out on our lives. We can't do anything about the past, we can just go through it again and again, and the future is completely unknown.

So the practice of mindfulness is the practice of being alive. When we talk about meditation techniques, we are talking about life techniques. We are not talking about something separate from us. When we talk about mindfulness and living with full attention, we are talking about the practice of spontaneity.

It is important to understand that this is not about achieving higher states of mind. We are not saying that the recent situation is not worthy of attention. What we're saying is that the immediate situation is accessible and nonjudgmental, and that we can see it as such by practicing mindfulness.

Sitting meditation practice

Now we can move on to the practice form. Firstly, how we feel about the meditation room and the cushion on which we are going to practice is very important. We treat the place where we sit as the center of the world, the center of the universe. At this point we proclaim sanity and sit on the meditation cushion as if we were sitting on a throne.

When we sit, we have a sense of pride and self-esteem. Legs crossed, shoulders relaxed. We feel the sky above us. At the same time, we have a feeling of the earth - as if something is pushing us from below. Those who find it difficult to sit on a cushion can sit on a chair. The main thing is to be comfortable.

The chin is lowered, the gaze is softly focused at a distance of one and a half meters in front of you, the mouth is slightly open. The main thing is that you feel comfortable, dignified and confident. If you need to move, move, change your position a little. This is how we work with our body.

And now the next step - a simple step really - has to do with our mind. The basis of the technique is that we begin to notice our breathing, we must feel our breathing. Breathing is taken as the basis of our mindfulness technique; it brings us back to the moment, to the present situation. Breathing is something that exists constantly, otherwise it is too late to start anything.

We focus on exhaling. We don't manipulate the breath, we just notice it. So we notice the exhalation, then we inhale, and there is a momentary gap, a gap, a space. And exhale again. There are different meditation techniques, but this one is really advanced. We learn to focus on the breath and at the same time allow space to emerge. We then realize that even though the practice is simple, we have countless ideas, thoughts and concepts about life and the practice itself. And all we do with them is name them. We simply note to ourselves, “thoughts,” and return to the breath.

So, if we are thinking about what we are going to do with the rest of our lives, we simply call it “thoughts.” Everything that comes up, we simply recognize and let go.

There are no exceptions in this technique: there are no good or bad thoughts. Even if you think how wonderful meditation is, it is still a thought. How great the Buddha was - “thoughts”. If you feel like you are about to kill the neighbor next to you, just say “thoughts” to yourself. No matter how far you go, they are just thoughts, return to the breath.

Face to face with all these thoughts, it is very difficult to be in the present moment and be steadfast. Our life has created a barrier from various storms, elements and emotions that try to push us out of our place and upset our balance. All sorts of thoughts pop up, but we just note the “thoughts” and don’t get distracted. This is called "staying where you are, just dealing with yourself."

Post-meditation practice

We continue to “stay in place” when we leave the room where we meditated and return to normal life. We maintain a sense of dignity and a sense of humor and, at the same time, ease in touch with our thoughts.

The main idea is to learn to be flexible. The way we interact with our thoughts accurately reflects the way we interact with the world. When we start meditating, the first thing we realize is how crazy our mind is, how crazy our life is. But once we have a sense of a quiet mind, when we can sit with ourselves, we begin to understand what wealth we have.

As we continue to practice, our awareness becomes sharper and sharper. This mindfulness actually permeates our entire lives. The best way to appreciate our world is to appreciate the sacredness of everything. We bring mindfulness and suddenly the whole situation becomes alive. This practice permeates everything we do. Nothing is excluded. Mindfulness permeates sound and space. It is an absolute total experience.

Shamatha ( zhi-gnas, being at peace) is a calm and stable state of mind, which includes the accompanying mental factor ( sems-byung, secondary awareness) feelings of physical and mental readiness ( shin-sbyangs, flexibility). It is a joyful feeling of being able to focus on any object for as long as we wish.

Shamatha remains firmly on an object or state of mind. This may be a sensory object, such as the breath, or a visualized mental object, such as a Buddha image. Indian master of the 4th or 5th century Asanga in the Anthology of Special Branches of Knowledge ( Chos mngon-pa kun-las btus-pa, Skt. Abhidharma-samuccaya) places special emphasis on focusing specifically on the mental object.

Following his instructions, the Gelug tradition usually uses a visualized Buddha image as the object of concentration.

The Kagyu and Sakya traditions also use objects that the Gelug school would classify as sensual - images of Buddhas, flowers, stones, and so on. This does not violate Asanga's injunction. According to traditions other than the Gelug, the objects of sensory cognition include only sensory information, such as fragments of colorful shapes, which are not clearly divided into “this” or “that”. Concentrating on a buddha image or a flower involves purely mental cognition, as we construct a buddha image or flower from these fragments with the help of the mind.

However, most meditation masters of all Tibetan traditions recommend choosing a Buddha image—either a visualized image or the image itself—as it helps our practice of safe direction (refuge), bodhichitta, and tantra. By focusing on the buddha figure, we can also focus on the good qualities of the buddha ( yon-tan). Then our concentration can be accompanied by belief in the fact ( dad-pa, belief) that Buddhas have these qualities, and we can also direct attention to them as qualities that we ourselves strive to acquire.

To achieve shamatha, one can choose other objects of concentration, direct attention to them in other useful ways, and accompany the concentration with other creative emotions and states of mind. For example:

With the four immeasurable states of mind ( tshad-med bzhi) – equanimity, love, compassion and joy – we focus alternately on ourselves, friends, strangers and those we don’t like.

With equalization and replacement of attitudes towards oneself and others ( bdag-gzhan mnyam-brje) we focus on ourselves and on everyone else, directing attention to everyone as equals. And, continuing our concentration, we direct our attention to others with greater care with which we previously treated ourselves, and to ourselves with less care with which we previously treated others. Shantideva gave an interpretation of these objects of concentration in the text “Entering the Path of Bodhisattva Behavior.”

With four close mindfulness placements ( dran-pa nyer-bzhag bzhi) we focus on the body as unclean, on feelings as suffering, on states of mind as impermanent and on all phenomena as devoid of true identities.

With the Four Noble Truths, we focus on the changing aggregates in terms of true problems and true causes of problems, and on our mind in terms of cessation and true paths.

On the other hand, the focus of our attention may remain undirected to a specific object ( dmigs-med). You can stay focused:

in a state of love and compassion, which is not directed at certain beings, but spreads to everyone, like sunlight;

on emptiness, when lack of direction means lack of direction towards true existence;

on the mind (mental activity) as such, without directing attention to the objects of knowledge, as if they existed in themselves.

The final method of concentration to achieve shamatha is used in mahamudra meditations ( phyag-chen, great seal) and dzogchen ( rdzogs-chen, great completeness). There are at least four main ways of this meditation:

- In the Mahamudra Karma Kagyu tradition, we primarily focus on generally accepted objects, created on the basis of information from each of our senses (the visual image of an orange, the smell of an orange, the taste of an orange, and so on), and then - on the visualized object. When we achieve stable concentration, we focus it on the mind as such, but without focusing on the mind as an object. We are in balance in the natural state of mind, which is happiness ( bde-ba), clarity ( gsal-ba) and nudity ( stong-pa).

- In the Sakya Mahamudra tradition, we look at the visual image and then focus only on the aspect of clarity ( gsal-ba) knowledge, which creates this cognizable appearance.

- In the Gelug Kagyu Mahamudra tradition we focus on the superficial nature ( kun-rdzob, conditioned nature) of the mind as on mental activity only the creation of cognizable appearances and cognitive involvement in them ( gsal-rig-tsam, only clarity and awareness).

- In the Dzogchen tradition of the Nyingma school, we quiet the mind in a natural state between thoughts.

No matter what object we choose, we must work with it until we achieve shamatha without changing it.

Video: Dr. Alan Wallace - "What is shamatha?"

To enable subtitles, click on the “Subtitles” icon in the lower right corner of the video window. You can change the subtitle language by clicking on the “Settings” icon.

Favorable conditions Arrow down Arrow up

To practice and achieve shamatha, six favorable conditions are needed:

- favorable place ( yul);

- weak attachment - to people, friends, loved ones, to food, clothing, to your body, to care, comfort, praise, blame, to sleep, and so on;

- satisfaction with what we have - food, clothing, weather, and so on;

- freedom from busy affairs ( ‘du-‘dzi), such as business and other worldly pursuits, gardening, cooking elaborate meals, idle conversations with fellow practitioners, telephone conversations, email correspondence, and so on;

- pure ethical self-discipline;

- freedom from intrusive preconceived thoughts ( rnam-rtog) about what we usually want to do: watching television and videos, using the Internet, listening to music, reading novels, studying astrological, medical literature, and so on.

Maitreya in "Filigree for the Mahayana Sutras" ( mDo-sde rgyan, Skt. Mahayanasutra-alamkara) gives five qualities of the first of these six favorable conditions (places):

- easy availability of food and water;

- excellent spiritual environment ( gnas) – the place must be approved and sanctified by our spiritual mentor or masters who have meditated there previously;

- excellent geographical location ( sa) - an isolated, quiet place, away from people who upset us, with a pleasant view of natural spaces, the absence of fascinating sounds, such as the sound of running water or the ocean, and a good climate;

- an excellent group of friends engaged in similar practices and either living nearby or practicing with us;

- that which is necessary for a happy union (Skt. yoga) with practice, namely, you need to receive complete teachings and instructions on practice in advance, and also think about and understand them in order to get rid of questions and doubts.

Five obstacles to concentration Arrow down Arrow up

Complete teachings and instructions on shamatha primarily involve detailed teachings on the five obstacles to concentration ( nyes-pa lnga) and the eight constituent mental factors ( ‘du-byed brgyad), which are necessary to overcome them. Maitreya described these obstacles and factors in Distinguishing Between the Mean and the Extremes ( dBus-mtha’ rnam-‘byed, Skt. Madhyanta Vibhanga).

Five obstacles to concentration:

1. laziness ( le-lo) three types:

- putting off meditation until later because we don’t feel like doing it ( sgyid-lugs);

- clinging to negative or insignificant actions or things ( bya-ba ngan-zhen), such as gambling, drinking, friends who are bad influences, going to parties, and so on;

- feeling of inadequacy ( zhum-pa);

2. forgetting guiding instructions or losing the object of concentration ( gdams-ngag brjed-pa);

3. breaks due to mental mobility or mental dullness ( bying-rgod);

4. do not apply counteractions to them ( 'du mi-byed);

5. do not stop using countermeasures when they are no longer needed ( 'du-byed).

Levels of mental agility and mental dullness Arrow down Arrow up

There are two aspects of mental retention ( 'dzin-cha) object of concentration: mental placement ( gnas-cha, mental stay) and creation of appearance ( gsal-cha, clarity). The last aspect creates the cognizable appearance of the object.

Agility of mind ( rgod-pa, excitement) – a subcategory of mind wandering ( rnam-g.yeng) or distractions ( ‘phro-ba) is a disturbance of mental stay on an object under the influence of passionate desire or attachment. There are two levels of mental mobility:

- Rough mental agility. Because the hold on the object becomes too weak, we completely lose mental abiding on the object.

- Subtle mobility of the mind. We maintain a mental hold, but it is not strong enough, and therefore an implicit thought about the object of concentration or about something else appears. Even if we do not have this hidden thought, because the holding is a little tighter than necessary, we feel impatience or an “itch” and want to leave the object of concentration.

Mental dullness ( bying-ba, dullness) - interruption of concentration due to a violation of the creation of visibility, a factor of mental retention. There are three levels of mental dullness:

- Gross mental dullness. The visibility factor is too weak to make the object visible, so we lose it. There may or may not be mental fog ( rmugs-pa) (heaviness in body and mind) and drowsiness ( gnyid).

- Moderate mental dullness. We cause the object to appear, but because the object is not held firmly, there is a lack of clear focus ( ngar).

- Subtle mental dullness. We create the appearance of an object with a clear focus, but because the mental holding is still not strong enough, the created appearance lacks freshness ( gsar). Any of these levels of lethargy can be classified as a state of “absence.”

Eight Components of Mental Factors Arrow down Arrow up

To overcome laziness, we need to apply the first four of the eight mental factors:

1. belief in a fact ( dad-pa), namely the benefits of achieving shamatha;

2. it leads to conscious intention ( ‘dun-pa) concentrate;

3. it leads to joyful zeal ( brtson-‘grus), when we are happy to put effort into something constructive;

4. it leads to a feeling of readiness ( shin-sbyangs), which gives us the flexibility to practice.

Shantideva talks about four pillars ( dpung-bzhi) and two forces ( stobs-gnyis), which allow you to develop joyful zeal:

firm determination ( mos-pa) – a firm conviction in the advantages of achieving a goal and the disadvantages of not achieving it, which gives rise to an unshakable desire in us to achieve the goal;

durability ( brtan), or self-confidence ( nga-rgyal), arises when examining our ability to achieve a goal: having made sure that we can really achieve it, we systematically make efforts to do this, even if we move towards the goal either faster or slower;

joy ( dga'-ba) means that we are not content with just a little success, but rejoice at progress along the path, feeling satisfied with our efforts;

rest ( dor) is a break in case of fatigue, but not because of laziness, but in order to freshen up;

natural acceptance ( lhur-len) – acceptance about what we need to practice and what we need to get rid of in order to achieve our goals, as well as about the difficulties associated with it, after we have realistically studied them;

self-control ( dbang-sgyur) – we control ourselves and make efforts to achieve what we want.

To overcome forgetfulness of instructions or loss of an object of concentration, one should apply

5. mindfulness ( dran-pa) – memorization, mental retention of the object of concentration ( dmigs-rten), similar to "mental glue".

To get rid of mental mobility and mental dullness we need

6. vigilance ( shes-bzhin), with the help of which we check the state of our mindfulness. If, due to gross mobility of the mind or mental sluggishness, the action of the "mental glue" weakens, so that we lose the object, then vigilance prompts restorative attention ( chad-cing ‘jug-pa’i yid-byed) focus on it again. In addition, vigilance strengthens or weakens mindfulness in cases of moderate and subtle mental dullness or subtle mental mobility.

To remove the obstacle of not using countermeasures, you need

7. willingness to apply counteracting factors ( 'du-byed), which arises from two forces that enhance joyful diligence: natural acceptance of what needs to be done and what needs to be gotten rid of, and self-control.

In order to avoid using countermeasures longer than necessary, you should

8. weaken counteracting factors ( 'du mi-byed). This also applies to being aware of when to rest and when not to exert too much effort.

Concentration and alertness as natural qualities of mindfulness Arrow down Arrow up

To achieve shamatha, you need to focus your main efforts on maintaining mindfulness (“mental glue”) on the object of concentration. This means that efforts should be made primarily to hold the object. With mental glue comes focus naturally. “Mental glue” and concentration are two descriptions of the same mental activity. “Mental glue” describes it in terms of mentally holding an object, and concentration in terms of placing the mind (mentally staying) on the object.

Moreover, if we compare the “mental glue” to the sun, then alertness naturally appears with it, like sunlight. In other words, if with the help of "mental glue" we can maintain a mental hold on an object, this implies that we check what state the hold is in automatically.

However, sometimes a second type of vigilance should be used, which makes a brief check of the state of the mental hold on the object. But at the same time, we use a small part of our attention without shifting its main focus from the object of meditation.

Nine stages of mental stability Arrow down Arrow up

There are nine stages of achieving the state of shamatha ( sems-gnas dgu):

- Mindset ( sems 'jog-pa) to the object of concentration. At this stage we can only establish, or place, attention on the object of concentration, but are not able to maintain it.

- Installation with some duration ( rgyun-du 'jog-pa). Here we can already maintain continuous mental presence on the object, but only for a short period of time before losing it. It takes some time to realize that we have lost the object of concentration and to regain attention.

- Recovery ( glan-te 'jog-pa). As soon as we lose our mental hold on an object, we are immediately able to recognize it and immediately regain attention.

- Close installation ( nye-bar 'jog-pa). At this stage we do not lose our mental hold on the object, but since there is great danger that subtle mental mobility in the form of hidden thoughts, as well as middle mental dullness, may arise, we need to make great efforts to maintain their countervailing forces.

- Taming ( dul-bar byed-pa). Here we no longer experience gross mental mobility, subtle mental mobility due to hidden thoughts, and gross and average mental dullness. However, by over-concentrating and going too deep within, we weaken the appearance-making factor that causes the object of concentration to appear. As a result, we experience a subtle mental dullness. We need to refresh and uplift ( gzengs-bstod) mental retention, remembering the benefits of achieving shamatha.

- Calm ( zhi-bar byed-pa). Although subtle mental dullness is no longer a great danger, because we have brought the mind into an elevated state, we become too agitated and the mental hold becomes too strong. Therefore, we experience subtle mobility of the mind - we feel an “itch”, we want to leave the object of concentration. To detect this and loosen the mental hold a little, you need to increase your vigilance.

- Complete calm ( rnam-par zhi-bar byed-pa). Even though the danger of subtle mobility or dullness of mind is minimal, we still have to make efforts to get rid of them completely.

- Unidirectionality ( rtse-gcig-tubyed-pa). At this stage, with only a little effort in applying the “mental glue” at the beginning, we can maintain uninterrupted concentration throughout the entire session, without any level of mental vacillation and dullness.

- Absorbed installation ( mnyam-par 'jog-pa). We can effortlessly maintain uninterrupted concentration throughout the entire session. This is the achievement of absorbed concentration ( ting-nge-‘dzin, Skt. samadhi).

We achieve shamatha when, together with absorbed concentration, we acquire the mental factor of a joyful feeling of mental and physical readiness to maintain perfect concentration on any object for as long as we wish.

Six forces Arrow down Arrow up

We move through the nine stages of mental stability, based on the following six forces ( stobs-drug):

- The Power of Listening to Instructions ( thos-pa'i stobs) allows us to reach the first stage.

- The Power of Contemplating Instructions ( bsam-pa'i stobs) brings us to the second stage.

- The power of mindfulness ( dran-pa'i stobs) helps to go through the third and fourth stages.

- The power of vigilance ( shes-bzhin-gyi stobs) contributes to the achievement of the fifth and sixth stages.

- The power of joyful zeal ( brtson-‘grus-kyi stobs) allows you to move on to the seventh and eighth stages.

- The power of full awareness ( yongs-su ‘dris-pa’i stobs) serves as a support for reaching the ninth stage.

Four Types of Attention Arrow down Arrow up

As we move through these nine stages of mental stability, we use four types of attention ( yid-byed bzhi). These are the four ways of mentally holding an object of concentration:

- Diligent attention ( bsgrims-te ‘jug-pa’i yid-byed) is used in the first two stages, when keeping the mind on an object requires considerable effort and control.

- Restorative attention ( chad-cing ‘jug-pa’i yid-byed) is applied from the third to seventh stages. Whenever errors occur, it returns our focus to the object, restores it.

- Continuous attention ( chad-pa med-par ‘jug-pa’i yid-byed) is used in the eighth stage. Thanks to it, we can concentrate on an object continuously.

- Spontaneous attention ( lhun-gyi ‘grub-pa’i yid-byed) is used in the ninth stage and allows you to maintain concentration on an object without effort.

cleaning the entrance gates. Above the entrance there is a khorlo, the earliest, according to historians and archaeologists, a Buddhist image symbolizing the Dharma - the Teachings of the Buddha. The wheel is believed to be an ancient Indian symbol of protection and creation, found for the first time in our history on the clay seals of the Harappan civilization (circa 2500 BC) as a solar symbol. The wheel, or chakra, is the main attribute of the Hindu god Vishnu, who maintains the established order in the Universe; its six-spoked disc, called the Sudarshana Chakra, represents the wheel of the manifest Universe - a symbol of movement, continuity and change, ever rotating like the celestial spheres. The chakra can be a weapon, in which case it has six, eight, twelve or eighteen sharp blades and is used as a throwing disc. In Buddhism, the wheel is the main emblem of Chakravartin (Sanskrit: “He who turns the wheel”) - the universal monarch who rules in accordance with the principles of Buddhist Teachings. The wheel is called Dharmachakra - the wheel of Dharma, i.e. Buddhist Teachings. Literally translated from Tibetan CHE-CHI KHOR-LO (Dharmachakra in Tibetan) means “wheel of transformation”, spiritual transformation. The rapid rotation of the wheel means rapid spiritual changes to which the Teachings of the Buddha lead. Comparing the wheel with the Chakravartin's throwing weapon reveals its ability to cut off obstacles and illusions. The three parts of the wheel - the hub, spokes and rim - symbolize the three aspects of Buddhist teachings: ethics, wisdom and concentration. Hub, i.e. the very center, the core of the wheel represents the Vinaya - the rules of discipline or ethics that concentrates and stabilizes the mind. The sharp spokes symbolize wisdom or discriminating awareness cutting through ignorance. The rim represents meditative concentration. It includes the rotation of the wheel itself and also facilitates it. The wheel with a thousand spokes, like the rays of the sun, symbolizes the thousand wonderful deeds and teachings of all Buddhas. The wheel with eight spokes symbolizes the Eightfold Path, as well as the spread of the Buddha's Teachings in eight directions - the four main cardinal directions and the four intermediate ones. The wheel as an auspicious symbol is made of pure gold extracted from the Jambud River flowing in our world system i.e. on the continent of Jambudvipa. It is usually depicted with eight Vajra-like spokes and a hub decorated with a triple or quadruple "joyful whirlwind" (Tib. GA-KYIL or GAN-CHIL), twisted into a spiral, like the Chinese Yin-Yang symbol. The triple ganchil signifies the Three Treasures: Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, or victory over the three poisons: ignorance, passion and anger, and in the context of the Dzogchen teachings - the Ground, the Path and the Fruit. The quadruple ganchil, corresponding in four different colors to the four primary elements and cardinal directions, symbolizes the Four Noble Truths, or, at the level of practice of the highest Tantras, the ascent and descent of the white and red drops of Bodhichitta (special essences of the subtle body, contemplated at the level of highest yoga) through the four chakras the central channel, generating the Four Joys. The rim of the wheel is depicted as a simple ring with small gold decorations on eight sides, sometimes designed as a setting with precious stones. A silk ribbon or scarf usually forms the drapery behind the rim of the wheel, and its lower part rests on a lotus base. If the golden wheel with eight spokes is depicted accompanied by two deer, then this symbol represents the first sermon of the Buddha's teachings in the Deer Park in Sarnath, near the city of Varanasi in India. This sermon is known as the First Turning of the Wheel of Dharma, when the Buddha expounded the foundation of all the Teachings and traditions of Buddhism - the Four Noble Truths and the content of the Noble Eightfold Path - to five ascetics who became the very first Buddhist monks, members of the Sangha - the community of practitioners of the Buddhist Teaching.

Every bad thought that arises in us essentially boils down to a delusion. Wisdom is needed to remove delusion. And not only wisdom, but clear awareness and good concentration. Without good concentration, without a sharp focus of the mind, eliminating delusions is simply impossible. During the process of concentration meditation, the mind becomes so clear and transparent that we are able to see the smallest particle of this world, so calm and happy that it cannot be compared with any other states of happiness.

When I was in the mountains, a friend came to me who was practicing one-pointed concentration. From it I saw that we can actually do this. But both for an entry-level Buddhist and at advanced stages, concentration is the most important practice. This man practiced meditation for three or four years in the mountains. And he practiced shamatha for two years and had already reached the fifth, that is, “continuous” level of concentration. Sometimes during meditation he thinks he is doing it for a short time, but in reality many hours pass. He is a good friend of mine, and when I went to visit him, he was always laughing and happy. I asked him how he was doing, he said that he had no reason to be unhappy. He has a good sense of humor and we joked with each other. When I looked at it, I saw that such practice could give advancement or at least bring happiness, joy and peace.

But when it comes to practice, it is extremely important to know how to practice correctly. Otherwise you won't make any progress.

What place is suitable for shamatha practice? If you are going to exercise intensively, it should be a very quiet, secluded place so that there is no danger to life and food can be easily obtained. In addition, you must be provided with everything that is necessary for practice, that is, knowledge. But we cannot immediately rush somewhere solitary. We can do a little bit at a time, and that's not bad either. I will tell you how to do this practice in everyday life so that you can progress gradually step by step. Even in the mountains, when people sit in solitude, it is recommended to start with short periods of meditation. Therefore, before retiring into solitude, it is useful to do this brief practice in everyday life, at least once a day.

When you practice meditation, posture is very important. Legs should be crossed. Of course, it may be difficult at first, but in the long run it is very useful. Still, for some people this is almost impossible, so you can simply sit on a chair, as comfortable as possible. In other cases, it is recommended to cross your legs. Hands should be folded at the level of the lower abdomen. The thumbs rest against each other, the right palm is placed on the left. It's the same for men and women. Shoulders should be straight, head slightly bowed. Take this pose. The eyes are half-closed. The mouth should not be completely open, otherwise the fly may fly in. (Laughter). But there is no need to close it completely, so that a bad taste does not appear in your mouth. The tongue should be raised to the sky. You should not be tense and your back should be straight. This is how we sit down.

Breathing is very important. If we do not take 21 breaths before starting meditation, then there will be so many thoughts in our heads that we will not be able to truly concentrate. So first we do a breathing meditation. Once in a meditative pose (called Vairocana pose), we simply focus on our breathing. When we exhale, we concentrate on what we are exhaling, and the same thing when we inhale.

I will explain the purpose of this meditation with an example. For example, small children play with a knife. You want to take it, but they won’t give it back. You show them something more interesting and they immediately drop the knife. It's the same with our mind. When we want to focus on an important object and tell our mind: “Focus!” - He doesn’t listen to us. And when we sit down to meditate, the mind wanders. To stop this, you need to do breathing meditation. Various thoughts and ideas appear in the mind. One thought, if allowed, gives rise to a multitude of others, and this happens endlessly. Therefore, it is important to simply drop it and shift your attention to something else. When we focus on breathing, our mind is distracted from its addictions, worries, anger and gradually calms down.

So, we sit down and begin to focus on our breathing: how we inhale, exhale, etc., and do this for a while. When we exhale and inhale, we count "ones", etc. And if you can stay focused on your breathing, without distractions, without any thoughts interrupting your concentration, up to 21 times, then your concentration is wonderful.

***

This breathing meditation is useful in daily life. Sometimes, when people are angry and don’t know how to cope with their irritation, they start drinking vodka. Why do they do this? Because when they drink, they stop thinking about their problem and think that the problem is solved. This meditation is a substitute for vodka! (Laughter). Think about it, this is a good saving on the household! – Saves money and does not harm your health. If you are angry, angry, try to leave the room and do this “21st breath meditation”, and you will feel less irritated and more peaceful.

Or one more thing. Some people have difficulty falling asleep and have trouble sleeping. Why is it difficult for them? Because they are overwhelmed by thoughts. One thought comes after another, and they cannot stop. They try to sleep, but thoughts keep coming and coming.

If you really want to fall asleep, then try to lie down and not think about anything. If you stop at one situation and think about it, it will prevent you from falling asleep. And don’t focus on the thought “I need to sleep,” this thought will give rise to other thoughts. Instead, focus on your breathing. Don't try to concentrate too much. If a thought comes to mind, let it come and go. And so, watching your thoughts, allowing them to go away, you will gradually fall asleep, and you will have a good sleep from meditation on breathing.

***

Let's go back a little to the topic of meditation posture. The pose is very important and must be remembered clearly and well. I want to briefly talk about the purpose of correct posture. Your back should be straight because if you lean forward or backward, it can interfere with your concentration. As explained on the tantric level, the central channel, Avadhuti, must be straight. If it is even slightly bent, then additional energy winds may appear in these places, which will distort the meditation process. The head should not be raised high and should not be lowered. If the head is raised more than it should be, then excessive excitement will appear, and if it is lowered too much, then there will be a blurring of thoughts and drowsiness. Shoulders need to be straightened. It is very important that the pillow you sit on is level. In this case, the back part should be slightly higher than the front. But if the pillow is tilted, then after sitting for a long time, tension will appear in the body and this will interfere.

And anyone who wants to seriously practice shamatha for any special purpose should also think about diet. Don't eat too little or too much, as this will interfere with concentration. You need to choose some measure of your food. Sometimes meat greatly contributes to concentration, but in small quantities and only sometimes. After all, those who meditate in the mountains live mainly on a vegetable diet, and a lot of energies arise in the body - energy winds, which leads to an imbalance. To somewhat balance the energy, you need to eat a little meat.

Earlier we talked about breathing meditation. In breathing meditation there is a regular practice and a special practice. I have already explained the usual practice, but seeing your interest, I decided to talk a little about special breathing meditations. Special breathing meditations are associated with yoga. Plus, they are good for your health if you do them in your daily life.

You need to visualize three internal channels in the body. The middle channel is white. It goes like this: it starts at the “third eye,” goes around the head, runs along the spine, and ends below the navel. The channels are small, very thin and twisted. The center channel is a little thicker. The right channel is red. It starts at the bridge of the nose and runs along the spine on the right side. In all chakras it is tied into knots. That is, the central channel is straight, and the lateral ones in the chakras are arched and tied into knots. The left channel is blue. It goes straight from the nose, tied into a knot at the crown chakra, then tied into a knot at the throat chakra, then the heart and navel. This is how you can roughly imagine the picture of these three channels. It's not that difficult. Then you visualize your left channel flowing into your right channel, like one tube into another.

Now we fold our hands. First the thumb, then bend all the others except the index fingers - they remain. And we put them on our knees. And then, raising our right hand, we first close the right channel with our right index finger. Before we start breathing, we try to clearly visualize the channel. We inhale three times. By inhaling with this triple inhalation, we visualize all the good energy of white color. All the good virtues of the Buddha enter us when we breathe and, passing through the left channel down to the level below the navel, cleanse this channel of all impurities. Then we exhale in a triple exhalation through the right nostril, closing the left nostril with our finger and visualizing that now the impurities are coming up the right channel and leaving our body from the right nostril. We do this three times.

Now let's start from the other side. Close the left nostril with your left finger and repeat the same process. We inhale through the right nostril, and as we inhale, all impurities expelled by the white light descend through the right channel to the junction of the channels. As we exhale, they rise up the left channel and, in the process of triple exhalation, leave our body through the left nostril. That is, we do the same process three times on the other side.

And now, for the third time, we visualize these two and the central channel. Then we inhale with a triple inhalation through both nostrils, and at the same time, white good energy enters through both nostrils into the right and left channels, and descending along them, expels all impurities. We then visualize the right and left channels entering the center channel. Impurities enter the central channel through them, rise through the central channel and, on exhalation, leave the body through the hole at the crown of the head. And before we begin to exhale, raising these impurities through the central channel, we literally hold our breath for a moment and then exhale.

This is truly a healthy meditation. When I meditated in the mountains, I did not go to doctors. This was my medicine. Since I came down, I have less time for meditation, and I have to see a doctor from time to time in Moscow. This preliminary exercise for developing concentration is very good for health.

The development of shamatha, that is, serenity of mind, is extremely important. Without the development of shamatha, neither the realization of the understanding of emptiness, nor the practice of tantra, nor the practice of mahamudra, nor the practice of dzogchen is possible. Therefore, shamatha can be called the foundation, the basis of all other realizations.

The great Atisha said that the development of shamatha is beneficial both for oneself and for the benefit of other beings. He explained that just as a bird cannot fly without wings, so a practitioner without shamatha cannot fly, either for his own benefit or for the benefit of others.

Shamatha is essentially a common practice between Hinduism and Buddhism. But in Buddhism, a variety of techniques for achieving samadhi are presented more fully. Compared to other achievements, shamatha is easier, but not at all as easy to achieve as it might seem. It also requires effort and constant practice. In addition, you need to know how to develop it correctly. Also, if you rush from one method to another, run from one road to another, you will not get anywhere. Take one method and master it properly. Then he will take you where you want.

First, about the object of meditation. There are many objects of meditation for shamatha. And the great masters, from the sutra point of view, usually suggest choosing the image of Buddha for meditation. At the tantric level, it is sometimes recommended to concentrate on the letter A or on the Clear Light, but this will be a little difficult for us. It is easier to meditate on the image of Buddha. Moreover, it is easier to imagine it not inside oneself, but outside, because we are all accustomed to thinking about the outside world.

My approach is to do something relatively easy. Then we will enjoy it and quickly move on. If we start right away with the difficult ones, then we simply won’t succeed.

Therefore, although from the point of view of Mahamudra, Dzogchen one should meditate on the mind, the very first step, which is to understand what the mind is, is a great difficulty. Although, from the Dzogchen point of view, this first step is the easiest. And in a higher sense, it is even more difficult to understand the nature of the mind. Therefore, you need to do simpler things first. I would not like you to think that I am criticizing Dzogchen. On the contrary, I myself try to practice Dzogchen, but find it extremely difficult. The practices of Dzogchen or Mahamudra, which in the Gelugpa school are essentially the same thing, are very difficult practices. If you first master the level of shamatha, then Dzogchen, Mahamudra, realization of emptiness, development of bodhichitta and renunciation, everything will become much easier. This will provide significant assistance in any area of practice.

In former times, shamatha was achieved in a period of six months to one and a half years. Firstly, because they did a very intensive practice, and secondly, because they knew how to do it. Now one of my friends, who tried to implement shamatha, was able to do it in three years. And this is also considered very fast. The achievement of shamatha significantly surpasses any other human achievement. A million dollars compared to achieving shamatha is nonsense. Because with the help of shamatha you can achieve such peace of mind, such clarity of mind that you would never buy for a million dollars. Already in this life it is extraordinarily beautiful. What can we say about future lives!

***

So, the object of meditation, the image of Buddha, should be small, the size of a thumb. Yellow color. And you should feel the rays emanating from it. However, you should not visualize it as a figurine. You must visualize a living, real Buddha, feel that he has weight. He is somewhere at arm's length from you. In addition, it is recommended to visualize the Buddha not too high and not too low, at the level of the forehead. It should be visualized as emitting rays because this radiation serves as an antidote to dullness of mind. And the heavy ones need to visualize it because it prevents the mind from wandering. Because it is heavy, it forces us to hold this Buddha more intensely. As Teacher said, if we tie an elephant to a thin post, he can easily pull it out with a rope. If the pillar is heavy and strong, then it is more difficult for the elephant of our mind to pull out such a pillar.

Why is the Buddha image visualized so small? This also has a reason. There are no random details in the visualization. We visualize it small in order to improve concentration: if we visualized a large Buddha image, attention would be scattered. So, this is an object of meditation for the development of shamatha.

Now that you have assumed the correct posture and you have an object of meditation, we begin to practice concentration. In this case, the eyes should be half-closed. Imagine that your eyes are completely open: can you visualize your own home? Perhaps it? When you close your eyes, it is much easier to visualize. But this has its disadvantages, if you keep in mind the long term of the activity, it will be worse in the long run. Therefore, we will try to close our eyes halfway and then visualize the image of Buddha. This will also be very difficult at first. To make the meditation process easier, it is very good to have a figurine in front of you at first. You look at this figurine from time to time, and then try to reproduce it in visualization. As the mind gets used to the image, it will become easier to visualize.

It will probably not be difficult for anyone to imagine the image of a friend whom you know and remember well. Your mind is very familiar with it. Also here: the more your mind gets used to the image of the figurine, the easier it will be to visualize it. Therefore, it is recommended to use the figurine first. Try not to strain your body, relax and concentrate in this state. It doesn't matter if you don't see it clearly. This is not necessary at first. If you picture it before you in your mind's eye, with at least some degree of clarity, try to hold it and remain there. If it disappears, try to hold it, then clarity will return. There is no need to try to make it clear with your own efforts - this will be a hindrance. If you still lose clarity, still hold it, just try to stay there. Feel that this is not a figurine, but a living Buddha. And don’t tense up under any circumstances – concentrate from a state of relaxation. If you strain, your mind will become tense, as will your body. Relax. Don't try too hard. Hold your knees with your hands. Do you feel the tension being released? The mind is clear and fresh. Now determine for yourself the need to concentrate for one or two minutes only on the image of the Buddha and nothing else.

This process is not easy, so after a while you will learn only to basically, roughly visualize the image of the Buddha. And when, with half-closed eyes, you can hold this image in front of you, it means you have reached the first level, which is called “discovering the object of meditation.”

This is the first success. You have already achieved some kind of achievement. I talk about these technical details because when we begin to practice, any achievement of some designated level gives us inner satisfaction. We feel that we are making progress, that we are on the right track.

One American woman, for example, has now reached the seventh level of samadhi, that is, when the elephant stands at the last turn to the right (see). This should give us all hope. If she could do it, why can't we? If this were achieved by one of the Tibetans, we could say: “Well, these are Tibetans - they have a tradition, a culture. Maybe they have something special in their blood.” And if a Westerner like you did it, then you should understand that you can do it too.

Why was she able to achieve such success? Because she approached it very skillfully. She studied with one great contemplative in Dharamsala, Geshe Lamrimpa. She had previously received shamatha teachings from another teacher, but when you begin to practice practically, it is very good to have an experienced master nearby, because during practice many small questions arise.

Well, now let's get to the heart of the matter. So, the first stage is discovering the object of meditation. It is preceded by a practice that we call “searching for the object of meditation.” First, when we look at the figurine, and then we try to visualize, this is called searching. Then when we have discovered the object of meditation, it is called discovery. Next, we need to hold the object of meditation - this is the third stage: “holding the object of meditation.” And the fourth stage is “staying with the object of meditation.” So, there are only four stages: search, discovery, retention and stay.

These four stages are very important. For they will help you achieve the first stage of the first level of concentration. If you can maintain the object of meditation for one minute, consider that you have reached the first stage of concentration. You may be able to do this in one or two weeks. You will certainly be satisfied and say, “Oh, I have reached the first step.” This will give you confidence that the instructions are correct. But in order to reach the first stage, you need to know what the errors of meditation are. In order to achieve samadhi, we must go through all the stages one after another. And in order to reach the first of these steps, it is necessary to overcome obstacles. In order to overcome them, we must understand what they are. And if you don’t know what the mistakes of meditation are, then there is no benefit from your meditation. It will just be a waste of time.

So, if you repair a TV and don't know what's wrong with it, you can spend all day resoldering end after end, and all that work will be a waste of time. Therefore, when we see teachers who can concentrate without any effort, and we compare ourselves, the inept ones, with them, it is clear that there are some reasons for this difference. I told you that in Buddhist teachings the main idea is that everything develops according to a cause-and-effect scheme.

So, there are five main mistakes in meditation. The first of them is laziness. She easily stops all of us. The second mistake is forgetting the object of meditation. This happens because the mind wanders off somewhere and we forget what we are contemplating. Then there is a dual obstacle: on the one hand - excitement, on the other hand - drowsiness and vagueness, when the thought blurs and ceases to be clear. The essence of the first is that, since we have attachments, the mind begins to be distracted from the object of meditation and follows the usual path, heading, for example, to family, home or other objects familiar to itself. When the mind is excited by stereotypical thinking, this error is called mental agitation. And mental dullness, literally translated, is the disappearance of mental clarity. When the dullness becomes stronger, we fall asleep. Then we have a very good meditation for an hour. (Laughter). – Without any interruptions or interference. These two obstacles together constitute the third error of meditation.

The fourth is that we do not apply the antidote to errors when it should be applied. So, for example, in the fifth, sixth and seventh stages the following can happen: we keep the object of meditation in consciousness, but at some point we feel that there is a loss of clarity. We see how it arises, small at first, but we do not apply the antidote. This mistake is typical for fairly high levels of meditation. It doesn't happen at first.

The fifth mistake of meditation is that we continue to use the antidote when it is no longer necessary. This may be in the eighth or ninth stage, although there is no need to use an antidote at these stages. This will only interfere with meditation. You relax and the mind should be relaxed. It's like an eagle taking flight. As he rises, he uses his wings, but when he reaches the desired height, he simply floats without the need to flap his wings. Also in the eighth and ninth stages of meditation.

These are the five main evils of meditation. If you have conquered these five errors, then you have achieved shamatha. If nothing prevents you from reaching this level, you will achieve it. In the first and second stages of shamatha, the goal is actually to eliminate these obstacles. When they are eliminated, you progress. So if, when repairing a TV, out of five faults you have eliminated the first two, then something will already appear on the screen. And once you eliminate the rest, the TV will work great.

It's important to know the antidotes to these five mistakes. People who are really serious about meditation will gladly pay a hundred dollars without hesitating to have me talk about these antidotes.

By the way, I want to note that Tibetan teachers always teach completely free of charge, and therefore students sometimes do not appreciate the Teaching, believing that it is always available. Therefore, it seems to me that sometimes it makes sense to somehow emphasize the value of the teaching. In the old days, when Tibetan Buddhists went to India to receive the Teaching, they had to overcome a lot of obstacles, and no one gave them the Teaching as easily as you. Usually the teacher answered: “I don’t know anything, move on.” Take the famous example of Marpa Lotsava. How much hardship he endured until, finally, Naropa began to teach him little by little! Before this, he made Marpa work hard to acquire virtues. And only after that he began to reveal the Teaching to him. It seems to me that in showing their compassion in this way, the Indian teachers demonstrated a very clever method, and it should be used now. So when I talk now, please don't think of it as something lying on the road. Please regard these teachings as extremely valuable. Fine?

***

There are eight antidotes for overcoming mistakes. The first four of them relate to the first mistake - laziness. It is very difficult to eliminate. But if you have an antidote, then eliminating laziness is easy.

The first of the antidotes is to reflect on the benefits that the achievement of shamatha can bring; - faith. The more you think about the merits of shamatha, the stronger your conviction will become that you need to cultivate it. And when there is faith and conviction in the virtues of shamatha, then inspiration to practice naturally arises.

This inspiration is the second antidote. It comes from belief in the virtues of shamatha. The more you understand that shamatha is wonderful, the stronger the desire to strive to achieve it. And when inspiration appears, enthusiasm also increases.

Enthusiasm, the third antidote, in this case we call pleasure, the pleasure of doing this practice. Those who don't like football don't think playing football is important. If they were forced to play, they would consider it a punishment. You have to run, someone can kick you, hurt you, it’s torture! What if you tell a boy about how great it is to be able to play football? You can tell him: “You will play like Maradona!” And he will be filled with enthusiasm and will kick the ball, despite fatigue or injury. And if he gets scratched, he won’t even notice it and will say: “I’m enjoying myself!”

It is sometimes difficult to get young children to do things they don't want to do. But if you infect them with enthusiasm, they will do this with pleasure. Also, if we compare the achievement of samadhi with the achievement of other goals, for example, wealth or fame, we will be able to understand that a million dollars or fame creates a lot of problems for us, that shamatha compared to these problems is like gold compared to other metals. And if we invest energy in achieving worldly goals, then we need to think: why not invest energy in achieving a much more valuable acquisition - shamatha? That's why I talk about this in such detail. We may spend a lot of time, but this is a very important thing, and I would like to convey it to everyone.

I myself was a very lazy boy. My mother urged me when I had to study. I didn’t like any kind of work; I had to be forced all the time. I ate and slept a lot. But it was thanks to the use of the antidote that when I became enthusiastic, I went to meditate in the mountains. If I had not become enthusiastic about using the antidote, I would have walked down the mountain in three days. What would I do there! In the mountains, I had to walk for half an hour just to fetch water. In other conditions, a person may find it painful to spend so much time fetching water. But it’s like playing football: if you have enthusiasm, you do it with pleasure, without noticing scratches and abrasions. That's how I enjoyed it. It all depends on psychology, on your attitude to what you are doing.

These instructions are extremely practical for our level. Imagine, for example, that you want to buy something here in St. Petersburg. Then they will explain to you what and how you can buy here. At the same time, they may explain to you what you can buy in Moscow or somewhere in India. This may also be interesting, but is not relevant at this point. Therefore, you would prefer to listen to what you can buy here, and then there.

The fourth antidote to laziness is self-soothing of the mind. Through faith we develop inspiration, and through inspiration comes enthusiasm. When enthusiasm drives us to continue and continue meditation, we develop shamatha step by step, going through stage after stage, until finally we achieve complete peace of mind, serenity. And then practice brings us pleasure greater than anything in this life. These are the four antidotes to the first mistake.

Now let's talk about the fifth antidote - against the second mistake. This is mindfulness. Mindfulness is the antidote to forgetting the object of meditation. If attention is not enough, you forget the object of meditation. And by developing mindfulness, you will be able to keep it in your attention.

When we develop shamatha, the first thing we need to do is remove laziness. Secondly, forgetting the object of meditation must be removed. Developing attention is the most essential practice for this. The attention you develop is extremely useful in everyday life. In order to develop attention, you do not need to sit in a meditative pose. Just watch your body, speech, thoughts every day: how you act, how you communicate with other people, what you think about. And with this you can develop your attention.

Then the third error is the pair: mental excitement and mental dullness. The antidote (indirect) to this is the development of vigilance. Through vigilance we notice that agitation or dullness arises in our consciousness. That is, she is like a spy who gives us information about what is happening. In order to eliminate agitation, you need to clearly understand its causes. The cause of agitation of consciousness is excessive tension in contemplation. In order to eliminate unnecessary tension, it is recommended to place the object of meditation slightly lower. Then we relax the stream of consciousness, and this helps to relax. Or you can slightly weaken the glow of the Buddha’s figure and thus somewhat relax your attentiveness.

Dullness and lethargy of consciousness arises due to the fact that we lose the intensity of contemplation, and the object of contemplation also sinks somewhat, and the glow weakens. Then we need to do the opposite - slightly raise the object of contemplation and intensify its glow. The use of these antidotes is extremely important in eliminating agitation and dullness in meditation, because they cannot simply be removed by hand.

The fourth mistake is not using the antidote when it needs to be used. And here you just need to use an antidote.

And the fifth mistake is using an antidote when it is no longer needed. In this case, you just need to let go, relax the mind, allow it to be in balance.

You see that out of these five errors, three are quite difficult to eliminate. When these three are eliminated, the fourth and fifth are eliminated more easily due to mastery of meditation and familiarity with it. Therefore, in the process of developing shamatha in the first stages it is actually difficult to manifest. In the future, as you progress, everything gradually becomes simpler.

Now I will explain the nine stages of shamatha development according to this picture. You see a monk. This is actually ourselves. And while we are not here yet, we only have to reach this first stage. Next there are only nine images of the monk. That is, through practice he develops his meditation and reaches the ninth stage, where he is depicted on horseback. Starting from the ninth stage, he gains physical peace, bliss, and tranquility. Another drawing where he is riding an elephant shows that he is achieving spiritual bliss. And the picture above, where the monk holds a sword in his hand, sitting on an elephant, shows the unity of shamatha - peace and vipashyana - comprehension of emptiness - their connection.

In this state, thanks to the conquest of the “elephant” of our mind and the achievement of the union of shamatha and vipashyana, i.e. serenity and comprehension of the Emptiness, he achieves Liberation from suffering - Nirvana. This highest level, the achievement of true happiness and bliss, is depicted right here, at the top of the picture. And we humans actually have the ability to achieve not just temporary, but genuine supreme happiness. Therefore, our real goal in this process of development is not just the achievement of shamatha, but the achievement of the highest goal, i.e. Liberation.

***

I will tell you now what, in fact, all this means. Look, the monk has a lasso and a hook in his hands. Lasso means mindfulness, awareness. And the hook means vigilance. The elephant is our consciousness, psyche. The black color of the elephant shows a state of excitement and darkness. Monkey means wandering of the mind. And the black color of a monkey indicates excitement. Look, at the first stage our consciousness is completely black, and the monkey is also completely black. What needs to be done to turn black into white? The noose is necessary in order to catch this elephant: throw a noose of mindfulness over it, tie it and catch it; hook with a hook and so lead to Liberation.

***

Now we will talk about the stages of development of meditation. It is very important to develop shamatha sequentially, from one stage to another, and for this you need to know all the stages. Otherwise, we will not know where we are, we will not notice what our progress is.

When developing shamatha, there are two periods of practice. This is the practice of meditation itself and the period between sessions. What is done during the meditation itself? This period is divided into preparation, meditation and completion. When we are preparing for long meditation, we need to prepare many different things in advance; this is a house, and food, and so on. But the most necessary thing is knowing what to do during meditation. If you are really going to practice meditation and achieve any success, such preparations are necessary. Therefore, do not rush into meditation. First you need to prepare, provide yourself with everything for success, and then you will receive pleasure and satisfaction from it. When we begin the practice of shamatha, we must prepare ourselves with the right motivation. Then, sitting, as mentioned earlier, comfortable, not slanted, you know how to sit in the correct meditation posture.

The first thing we do is do a breathing meditation. There are two types of this meditation - ordinary and unusual. You can do any, but you don’t need to spend too much time breathing. When you do a breathing meditation, it is important to relax. If you are very serious about meditation, your posture during meditation and you become tense, then even your body will take a tense posture. It doesn't provide any benefit. You need to relax your mind and body, they should be free. If there is sometimes tension in the shoulders, that too should be released. Now we begin the actual meditation. We take a Buddha figurine and look at it, and it is important to have a figurine that is neither small nor large. First we look at it and try to recreate it in our mind’s eye in front of us. After you have considered and begin to reproduce this image, there are four stages: finding the object of meditation, discovering, holding and staying on the object.

When you have discovered an object and begin to hold it, then after a short period of time you lose it, the mind goes away. Then you again return the mind to this object, discover, hold, stop, abide on the object of meditation. Soon the mind again loses its object, and attentiveness is lost. We bring the mind back again. - This is how we progress.

When you begin to engage in the process of meditation, you find that more and more thoughts appear in your mind, more even than there were before the meditation. But this is a wrong impression. In fact, it is similar to how we pass traffic on the street without noticing it. But when we start looking closer, we see how many different cars there are and how they move. Also, when doing meditation, we simply discover our state of consciousness. This definition of our state of consciousness is the first stage of shamatha. And so you do over and over again, bringing your mind back to the object and improving your concentration. When we are able to locate an object, hold it and remain on it for at least one minute without distraction, without interruption in meditation, this means that we have reached the first stage. It's in the picture at the very bottom. Until then, we had not yet taken the right path.

This first stage is called "settling the mind." It is not easy to force your mind to hold an object for even one minute. Pure meditation is difficult to achieve. Moreover, when we try to hold an image in front of us, we tend to see it very clearly. This desire to see the picture very clearly is a hindrance. Let you have a very rough image at first, but it is important that the mind holds the object, stays on it. This is how progress in meditation will occur. But in the beginning, as the great teacher Tsongkhapa said, the desire to see an object clearly is a hindrance. A gradual clarification of the image will come later. Little by little everything will improve.

The more we meditate, the longer we can remain focused. In the beginning we go through four stages, and then when we lose the object and get it back again, there is no point in going through all four stages again, as in the beginning. It is enough to simply look for this object and stay on it. So when watching TV, we just turn our gaze to the screen, and here we are in the screen. It's the same in this meditation. And if you go through all four stages again when the mind loses the object, then this can become a hindrance. A side effect of this meditation is to gain clarity of mind. If there is an improvement in meditation, then memory improves and the mind becomes clearer.

Mind wandering, which is different from agitation, can create a problem. Mind wandering means the following: when you do meditation, the Buddha image suddenly becomes large, then reduces its size to small, changes its color, etc. This is called mind wandering. And for those who are familiar with the different forms of Buddha, this image can turn into yidams, meditative deities. This is the same wandering of the mind, despite the fact that the images may be good. Some Western people, contemplating the image of Buddha, allow it to transform, for example, into Avalokiteshvara, or into some other forms. They like these transformations, but in fact these fantasies do not give a real effect in their work - this is one of the mistakes.

Look at this picture again. The elephant of consciousness, which is completely clouded, is led by a monkey, that is, wandering and agitation. What need to do? You need to hook the elephant and try to tie it to the column. Who does this? This is done by the training mind, the restraining mind - that is, you yourself. To curb you need two things: a lasso and a hook. You throw a rope over the elephant and thus retain your consciousness. At first, the rope of attention is not strong, and the elephant of the mind can break it. Therefore, we must make the rope of our attention stronger and stronger. Then the elephant can be tied to the post of the object of concentration for a long time.